The data visualizations on this website are too large for mobile devices and small screens. For best results, please visit gspdrywells.com on a PC.

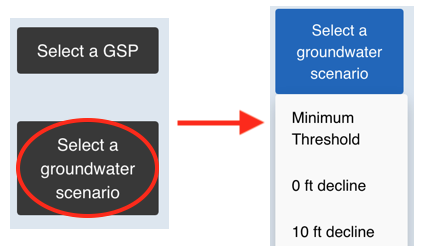

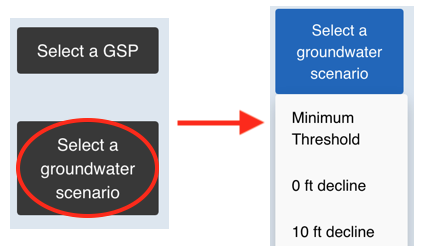

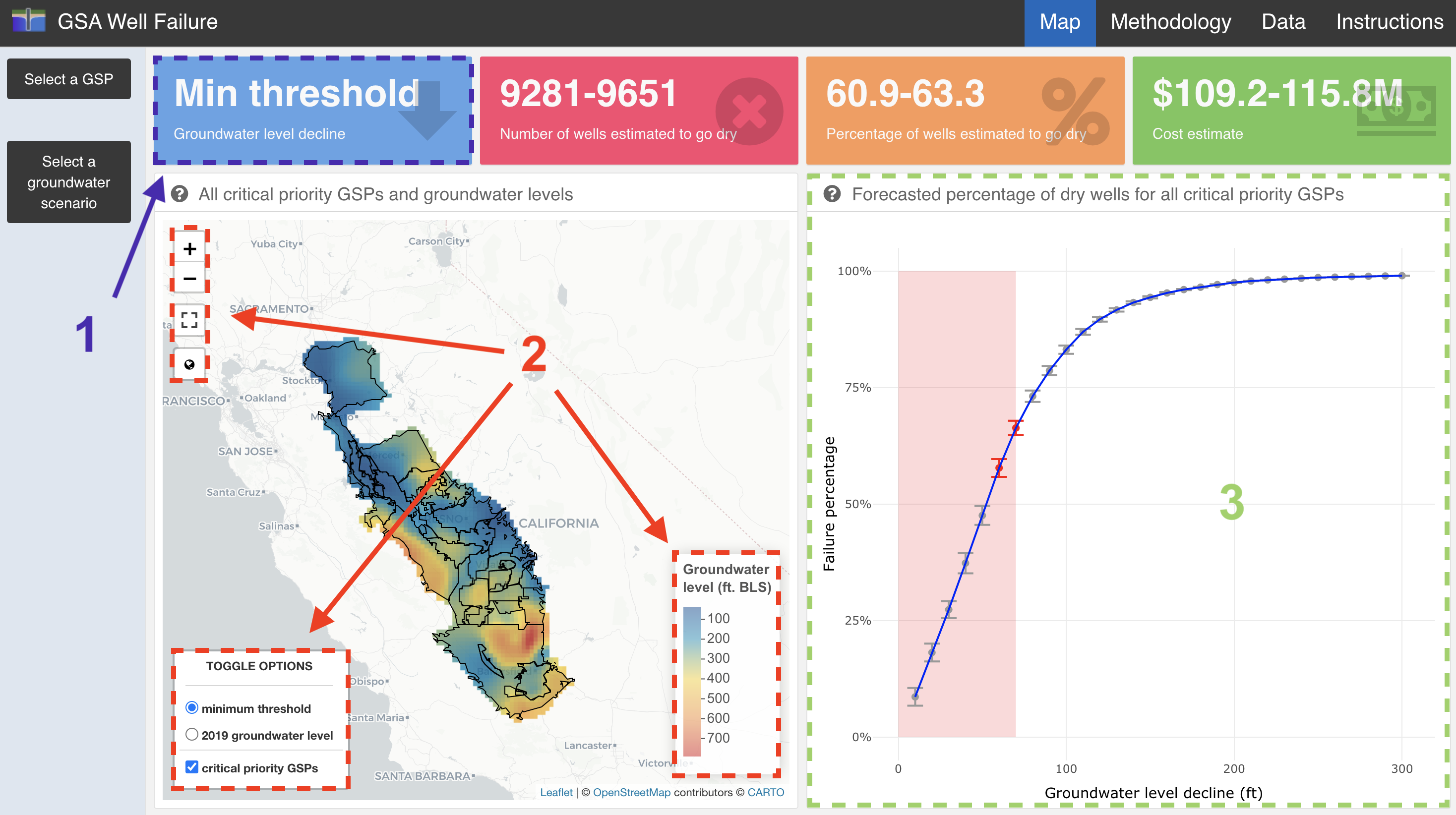

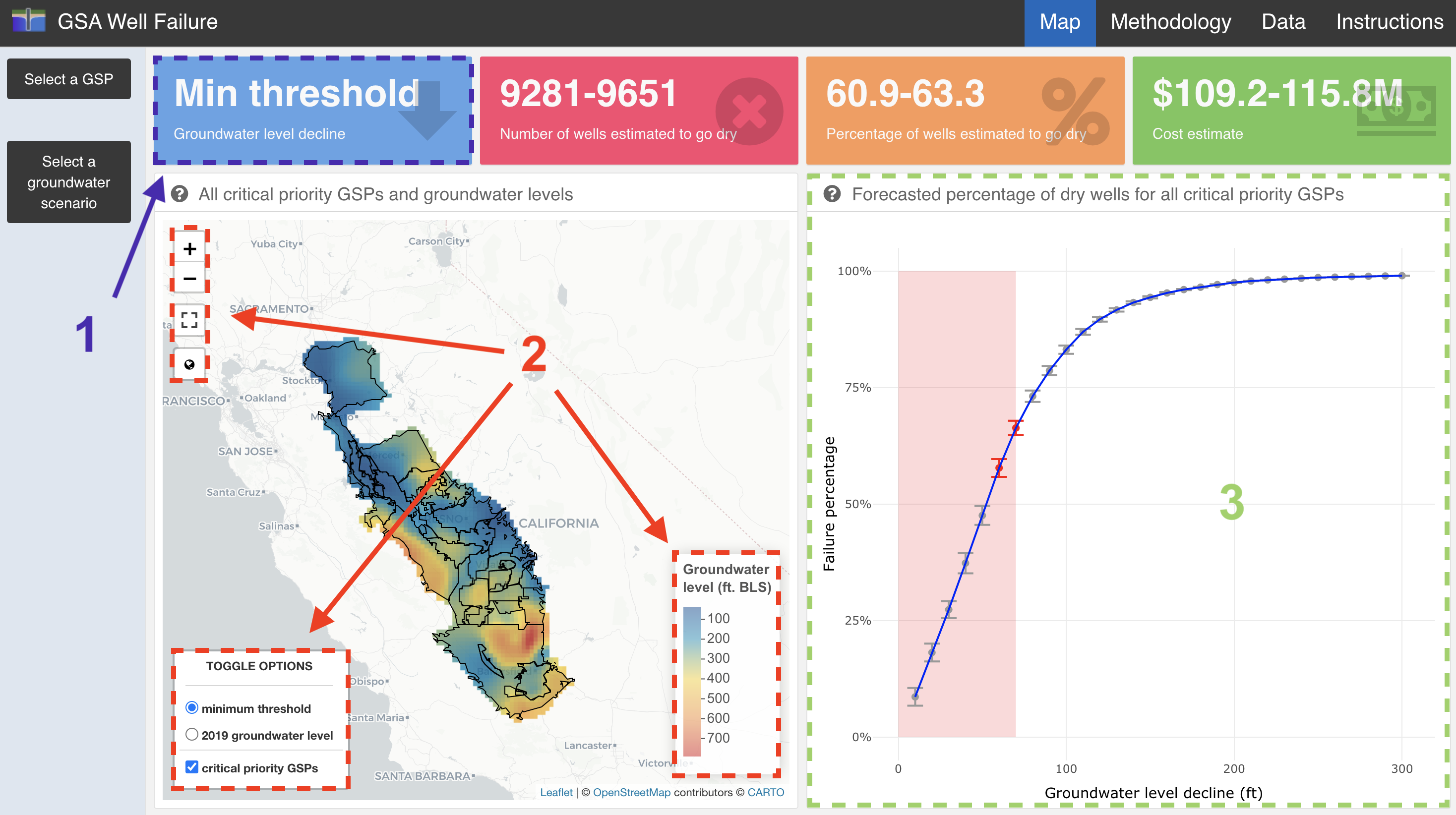

The Groundwater level decline shows how much lower the water level in the aquifers is, depending on the “groundwater scenario” selected. You have the option of choosing the “minimum threshold” that the GSP has selected in its Groundwater Sustainability Plan, or you may also choose how many feet below the 2019 groundwater level you want to see. For example, you can choose to see how many wells will go dry if the groundwater level is lowered by 10 feet, 20 feet, and more, up to 300 feet.

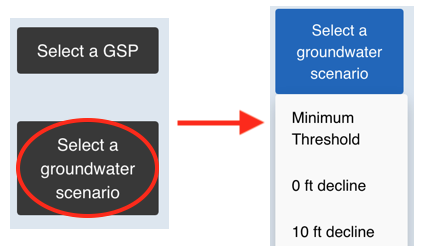

To view alternate groundwater level decline scenarios, click the “Select a groundwater scenario” button on the left-hand sidebar, scroll to the desired scenario, and select it from the list.

The Number of wells estimated to go dry is the number of private domestic wells that will go dry, or fail, because of the “groundwater scenario” chosen for the “selected GSP(s)”. Uncertainty in estimated pump location is responsible for the high and low dry well estimates.

The Percentage of wells estimated to go dry is the percent of domestic wells that will go dry out of all of the domestic wells in the selected “selected GSP(s)”, for the selected “groundwater scenario”.

The Cost estimate is the estimate of how much it will cost to lower pumps and deepen domestic wells that have gone dry at the selected “groundwater scenario” in the “selected GSP(s)”.

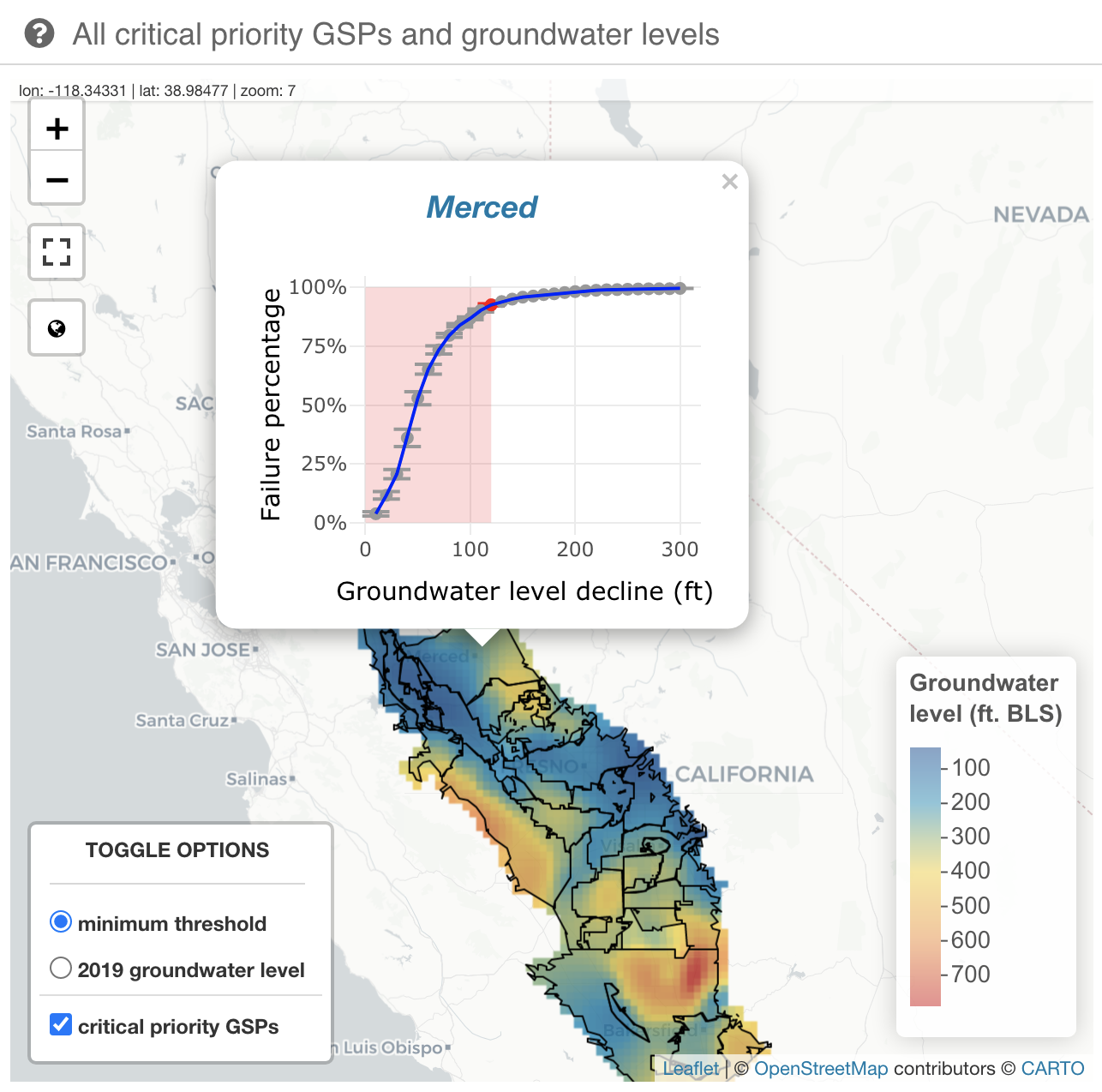

This plot shows the percentage of failing wells (y axis) for a given groundwater level decline relative to the 2019 groundwater level (x axis).

The red shaded region shows the user's selected groundwater level decline. If the minimum threshold scenario is selected, the closest groundwater level decline scenario(s) that correspond to a similar number of failing wells is shown.

Hover on points to well failure statistics associated with various degrees of groundwater level decline.

This map shows the minimum threshold surface and the average 2019 groundwater level in feet below land surface (ft BLS). Red indicates a greater depth to groundwater.

Toggle between the minimum threshold surface and 2019 groundwater level and hover on GSP areas to see their name.

On the home page, click GSP areas to see a plot of how many wells are expected to fail as groundwater levels fall.

On GSP-specific pages, active ( blue marker) and failing ( red marker) well locations are shown. Click on markers to see well attributes.

Millions of Californians rely on drinking water obtained from private domestic wells, which are vulnerable to drought and unsustainable groundwater management. Groundwater planning under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) aims to curb the chronic lowering of groundwater levels, which is known to increase domestic well failure. However, SGMA planning is decentralized, and thus, it is difficult to anticipate regional scale impacts to domestic wells resulting from water management decisions across numerous independent agencies. Here, we compile the minimum thresholds specified in the groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) from 25 groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) in “critical priority” basins, and estimate the magnitude, spatial distribution, and cost of domestic well failure that would result if minimum thresholds are reached. Well failures are quantified and characterized in order to support the assessment of whether such failures are significant and unreasonable, and to inform the development of well protection programs. Additionally, we evaluate well failures under uniform groundwater level decline ranging from 10 to 300 ft below the average 2019 groundwater level in order to present alternative management scenarios that may be compared against the minimum threshold scenario. In the critical priority basins we examined, we observe significant domestic well failure if minimum thresholds are reached that range from 12-99% failure in individual GSAs. Well failure across all GSAs combined under specified minimum thresholds is estimated to be 61-63%, or 9,281 - 9,651 domestic well failures at a cost of $109.2 - 115.8M. Well failure is most severe in areas where groundwater levels are already low due to historical overdraft, and where large concentrations of relatively shallow domestic wells are located. Possible well protection measures include regional groundwater supply and demand management (e.g., managed aquifer recharge and pumping curtailments that increase groundwater levels), well protection funds that internalize well refurbishment and replacement costs, and domestic supply management, (e.g., connecting rural households to more reliable municipal water systems).

Suggested Citation:

Pauloo, R., Bostic, D., Monaco, A. and Hammond, K. 2021. GSA Well Failure: forecasting domestic well failure in critical priority basins. Berkeley, California. Available at https://www.gspdrywells.com. (Date Accessed)

Around 1.5 million Californians depend on private domestic wells for drinking water, about one third of which live in the Central Valley (CV) (Johnson and Belitz 2016). Private domestic wells in California's CV are more numerous than other types of wells (e.g., public or agricultural), and tend to be shallower and have smaller pumping capacities, which makes them more vulnerable to failure due to groundwater level decline (Theis 1935; Theis 1940; Sophocleous 2020; Greene 2020; Perrone and Jasechko 2019).

During previous droughts in California, increased demand for water has led to well drilling and groundwater pumping to replace lost surface water supplies (Hanak et al 2011; Medellín-Azuara et al 2016). Increased pumping lowers groundwater levels and may partially dewater wells or cause them to go dry (fail) altogether. During the 2012–2016 drought, 2,027 private domestic drinking water wells in California's CV were reported dry (Cal OPR 2018). Despite the social and economic value of domestic wells, and the clear linkages of well failure to regional groundwater development, few solutions and data products exist that address the vulnerability of private domestic wells to drought and unsustainable groundwater management (Mitchell et al. 2017; Feinstein et al. 2017).

The lack of well failure research in California until recent years is largely because well location and construction data (well completion reports, or WCRs) were only recently made public in 2017. The released digitized WCRs span over one hundred years in California drilling history and informed the first estimates of domestic well spatial distribution and count in the state (Johnson and Belitz 2015; Johnson and Belitz 2017). Since then, these WCRs, provided in the California Online State Well Completion Report Database (CA-DWR 2018), have been used to estimate failing well locations and counts (Perrone and Jasechko 2017), well depths (Perrone and Jasechko 2019), domestic well water supply interruptions during the 2012–2016 drought due to overpumping, and the costs to replenish lost domestic water well supplies (Gailey et al 2019). Recently, a regional aquifer scale domestic well failure model for the Central Valley was developed by Pauloo et al (2020) that simulated the impact of drought and various groundwater management regimes on domestic well failure. In this work, we extend the model developed by Pauloo et al (2020) to estimate well failures in critical priority groundwater basins in California.

California's snowpack is forecasted to decline by as much as 79.3% by the year 2100 (Rhoades et al 2018). Drought frequency in California's southern CV, also the location of greatest domestic well density, may increase by more than 100% (Swain et al 2018). A drier and warmer climate (Diffenbaugh 2015; Cook 2015) with more frequent heat waves and extended droughts (Tebaldi et al 2006; Lobell et al 2011) will coincide with the implementation of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA 2014), in which critical priority basins have already submitted groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) that specify groundwater level minimum thresholds. These minimum thresholds signify the groundwater elevation at which undesirable impacts to beneficial users of groundwater, such as domestic wells, are anticipated to occur. Although methodological approaches to estimate well failure exist today, these were not widely understood during the development of GSPs in critical priority basins, and hence, a basic understanding of how groundwater minimum thresholds will impact well failure was unknown during the planning process. Two recent studies have shown that widespread and significant domestic well failure would result if minimum thresholds were reached in critical priority basins.

In this research, we predict the spatial distribution, count, and cost of domestic well failure in California's critical priority basins, focusing on groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) as our unit of observation. We also evaluate uniform groundwater level decline scenarios from a roughly present day (2019) average groundwater level to compare the impact of these alternate management scenarios. Lastly, we compare our results to those of Bostic et al (2020), and EKI (2020) then provide a dataset of our findings to enable further analysis and incorporation of domestic well protection measures (Islas et al, 2020) into ongoing GSP development and planning over the SGMA implementation period.

We use well completion reports from 943,469 wells from the California Department of Water Resources (CA-DWR 2018), seasonal groundwater level measurements (CA-DWR 2020) from the year 2019 in the CA-DWR Periodic Groundwater Level Measurement database, and minimum thresholds reported at representative monitoring points specified in GSPs submitted in critical priority basins.

We estimate the groundwater depth below land surface in the unconfined to semiconfined aquifer system for measurements taken at an initial condition (2019), and the reported minimum thresholds at representative monitoring points specified in GSPs submitted in critical priority basins.

The average 2019 groundwater level initial condition is based on seasonal (spring and fall) groundwater level measurements (CA-DWR 2020) and reflect the aquifer system from which many domestic wells draw water from. The minimum threshold surface was determined by reviewing 41 GSPs and 973 unique monitoring wells with specified minimum thresholds, detailed in (Bostic et al 2020).

We log-transformed and applied ordinary kriging to the 2019 and minimum threshold groundwater level measurements to normalize the data distribution, suppress outliers, and improve data stationarity (Deutsch C.V. and Journel 1992; Varouchakis 2012). Since the expected value of back-transformed log-normal kriging estimates is biased (not equal to the sample mean), we apply a correction (Laurent 1963; Journel A.G. and Huijbregts 1978):

\[ g = k_0 \cdot exp \Big[ ln(\hat{g}_{OK}) + \frac{\sigma^2_{OK}}{2} \Big] \]

Where \(g\) is the corrected and back-transformed groundwater level, \(\hat{g}_{OK}\) is the ordinary kriging estimate, \(\sigma^2_{OK}\) is the kriging variance, and \(k_0\) is the correction factor, proportional to the ratio of the mean of the sample values to the mean of the back-transformed kriging estimates.

Thus, we generate two surfaces: an initial condition representing 2019 average conditions, and a final condition representing the minimum threshold.

Lastly, we define a set of 31 uniform groundwater level decline scenarios ranging from 0 to 300 feet, which we subtract from the 2019 groundwater level. In contrast, the minimum threshold surface is directly kriged from 865 minimum thresholds specified at specific monitoring wells in GSAs. The uniform decline scenarios are used to evaluate the well failure that would result from the given amount of groundwater level decline, and may be compared to the minimum threshold scenario, as well as other decline scenarios to facilitate informed decision making.

The initial set of wells to consider are a subset (n = 15,368) of all domestic wells. Wells are removed based on the year in which they were constructed, and their estimated pump location relative to the initial groundwater level condition.

Two previous studies estimate well retirement ages at 28 years in the Central Valley (Pauloo et al 2020), and 33 years in Tulare county (Gailey et al 2019), thus, we use the average of these two studies and remove wells older than a retirement age of 31 years.

Wells dewater and experience reduced yield when the groundwater level approaches the level of the pump. However, for the purposes of this study, we assumed wells maintain net positive suction head (Tullis 1989) required for wells to provide uninterrupted flow until groundwater falls below the estimated pump location. Pump locations and associated 5 and 95% confidence intervals are estimated via a linear model at the Bulletin 118 subbasin scale for all domestic wells in the WCR database, as detailed in Pauloo et al, 2020. The initial set of wells to consider omits wells with a pump location shallower than the 2019 groundwater level initial condition – these wells are not considered because they are dry at the initial condition.

The set of 15,368 initial wells, neglecting retired wells and wells dry at the 2019 groundwater level initial condition, are all initially considered active.

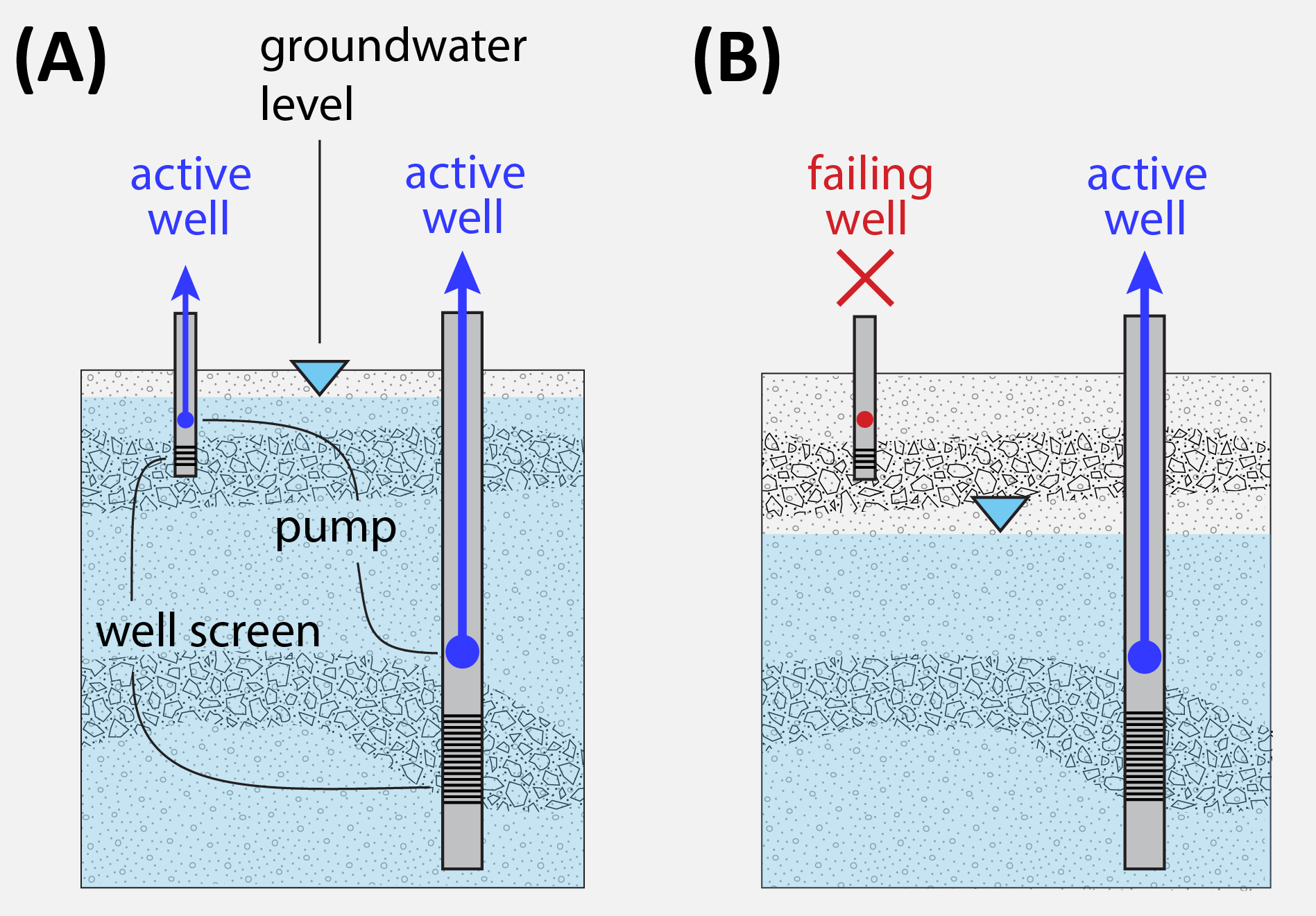

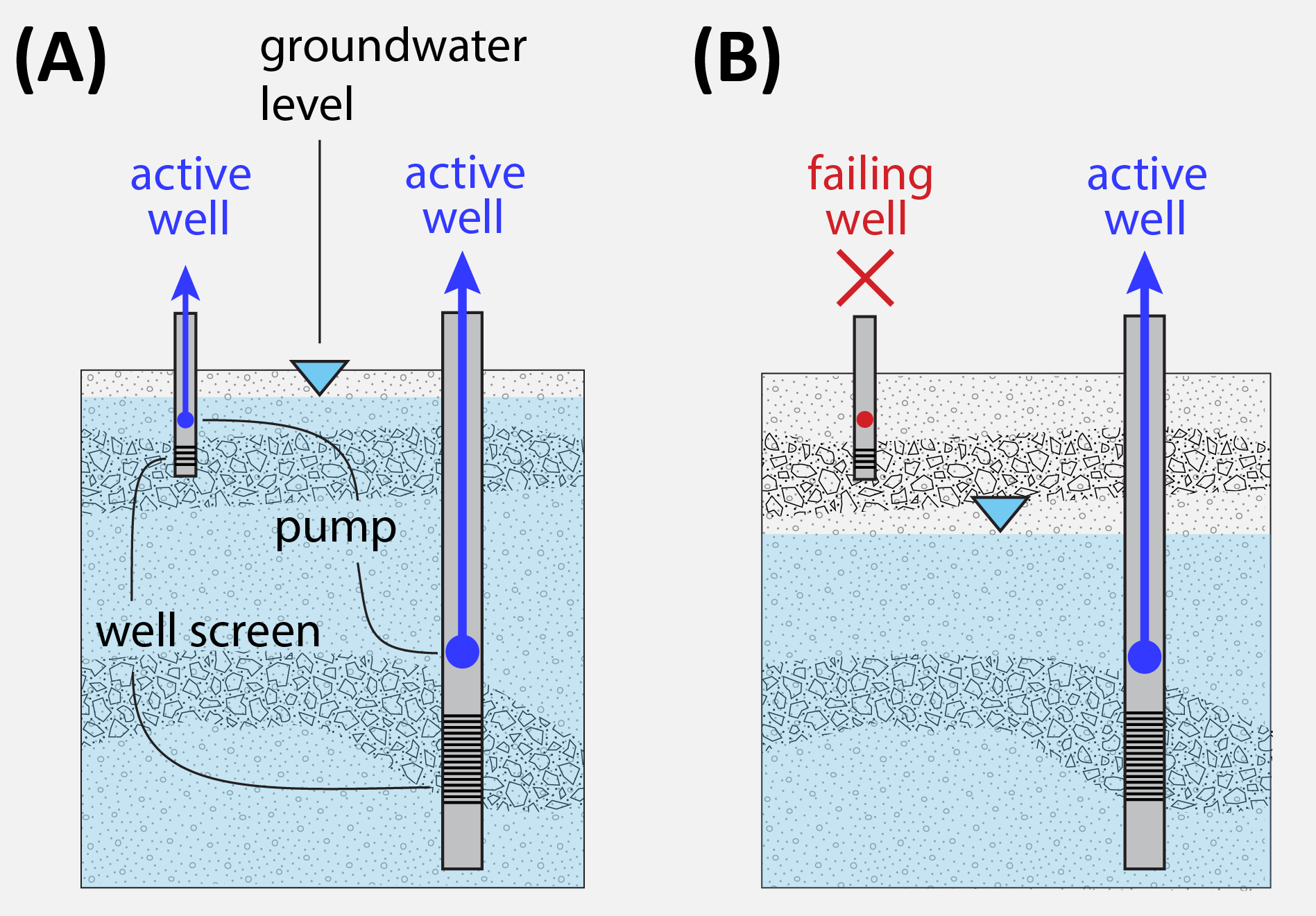

Next, we distinguish between two classes of well status: active and failing. We evaluate well failure at the minimum threshold surface, and at 30 uniform decline scenarios ranging from 10-300 ft below the 2019 initial condition. Active wells have a pump location deeper than the groundwater level and failing wells have a pump location shallower than the groundwater level. We propagate uncertainty from the pump location estimate via the 5 and 95% confidence intervals of pump location into the estimate of failing and active wells.

Figure 1: A conceptual model of well failure from Pauloo et al, 2020. (A) groundwater level is shallower than the pump location of the two wells and both are active, (B) the shallower well fails because the groundwater level falls below the level of the pump, but the deep well remains active.

In order to compute costs, we consider that failing wells differ in the remaining depth between the pump location and the total completed depth of the well. Once a well fails, it is assumed that the remediation action of lowering the pump to the total completed depth of the well takes place, at a cost of USD $100 / ft. If the groundwater level falls below the total completed depth of the well plus an operating margin of 30 ft, a second remediation action is assumed to take place, and the well is deepened by 100 ft at a cost of USD $115/ft. These costs are derived from well failure studies by Gailey et al., 2019 and EKI, 2020.

We neglect costs associated with increased lift, as these constitute around 1% of total costs estimated by EKI, 2020. We also neglect costs associated with screen cleaning, as this action is unlikely to yield significant additional water when groundwater levels have fallen below pumps.

In the critical priority basins examined in this research, we estimate significant domestic well failure if minimum thresholds are reached. On the order of 12-99% wells are projected to fail in individual GSAs, and well failure across all GSAs combined is estimated to be 61-63%, or 9,281 - 9,651 domestic well failures, at a cost of $109.2 - 115.8M. Well failure is most severe in areas where groundwater levels are already low due to historical overdraft, and where large concentrations of relatively shallow domestic wells are located.

There is a wide range in the difference between minimum thresholds across GSAs. Some GSAs have set minimum thresholds relatively deep compared to 2019 conditions, whereas others have been more conservative and set shallower minimum thresholds which generally lead to lower estimated well failures.

The 2019 groundwater level initial condition, the minimum threshold surface, and the locations of estimated active and failing wells per scenario are available in the interactive map on the GSA Well Failure web dashboard. Users can select a groundwater sustainability agency to focus on results for a particular management zone, and a groundwater level decline scenario ranging from the minimum threshold, to 0-300 feet of decline relative to the 2019 initial condition. All of the input data and output model results are available for download on the data tab as csv files. Users can also automate the data retrieval of these data via R or Python. The current CA-DWR Periodic Groundwater Level Measurement database is available online for download from the California Department of Water Resources.

Domestic wells, particularly in California's Central Valley, tend to be privately owned and adjacent to or within areas of concentrated groundwater extraction for agricultural and municipal use. Due to their relatively shallow depth, these wells are vulnerable to failing when water levels decline due to drought or unsustainable management. With the passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, local groundwater sustainability agencies will develop sustainable management criteria including minimum thresholds and objectives, codified in monitoring networks that are intended to measure progress towards, or deviance from, sustainability goals. These sustainable management criteria may or may not include domestic wells, owing to a lack of data, models, and systemic understanding.

Our estimates of domestic well failure count, percentage, and cost agree with other studies (Table 1). Notably, even though the three studies use have different initial well counts, they arrive at similar well failure precents. The nearly threefold higher cost estimate upper range estimated by EKI (2020) compared to this study's metric may be explained by the additional wells considered, and to a less extent, because this study did not consider screen cleaning and increased lift costs. Differences in well failure count estimates may be attributed to the initial set of wells considered, groundwater level initial condition, well retirement age, and the threshold at which failures are evaluated (e.g., pump location, total completed depth, total completed depth plus an operating margin). It is critical for future modeling efforts that these parameters are understood, standardized, and evaluated in terms of their sensitivity on model output. Nonetheless, across all studies, estimated well failures assuming minimum thresholds are reached range from the thousands to just over ten thousand, and may come at a cost of $1-3 or more million USD.

Table 1: Comparison of well failure statistics across three studies, including this one, that estimate domestic well failure in critical priority basins, assuming the specified minimum threshold is reached.

| Study | Retirement age (yrs) | Groundwater level initial condition (yr) | Initial well count | Well failure count | Well failure percentage | Estimated Cost ($M USD) | Count of people impacted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| this study | 31 | 2019 | 15,368 | 9,281-9651 | 61-63% | 109-115 | NA |

| Bostic et al (2020) | 29 | 2019 | 8,206 | 5,416 | 66% | NA | 55,698-222,792 |

| EKI (2020) | NA | NA | 24,500 | 12,000 | 49% | 88-359 | 106,000-127,000 |

To support efforts to protect domestic wells, the input data and modeling results are made available on the data page, and the R code that implements this model is available on Github.

This study suggests that minimum thresholds for groundwater level set in critical priority basins may lead to thousands of well failures over the SGMA implementation time period from the present day through 2040. However, groundwater sustainability plans in these basins may not estimate well failure or define well protection plans or project management actions that address well failure. Estimated domestic well failure and refurbishment or replacement costs across the implementation time horizon may be small in comparison to the economic value of groundwater, yet studies linking these quantities are lacking. Possible project management actions to protect wells include regional groundwater supply and demand management (e.g., managed aquifer recharge and pumping curtailments to increase groundwater levels), well protection funds to cover well refurbishment and replacement costs, and domestic supply management, such as connecting households to reliable municipal water systems.

This work is made possible with support from the AI for Earth Innovation Program Grant provided by Global Wildlife Conservation and Microsoft Corporation (see press release).

[2] CA-DWR. (2018). California Online State Well Completion Report Database. Available at: https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/well-completion-reports. Accessed January 1, 2018

[3] CA-DWR. (2020) Periodic Groundwater Level Measurement database. Available at: https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/periodic-groundwater-level-measurements. Accessed March 1, 2020

[4] CA-OPR (2018). Observed domestic well failures during 2012-2016 drought dataset obtained via an agreement with the California Governor’s Office of Planning and Research. Sacramento, CA. Accessed May 6, 2018

[5] Deutsch, C. V., & Journel, A. G. (1992). Geostatistical software library and user’s guide. New York, 119(147).

[6] Diffenbaugh, N. S., Swain, D. L., & Touma, D. (2015). Anthropogenic warming has increased drought risk in California. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(13), 3931-3936.

[8] Feinstein, L., Phurisamban, R., Ford A., Tyler, C., and Crawford, A. (2017). Drought and Equity in California Drought and Equity in California. Pacific Institute. Oakland, CA.

[9] Gailey, R.M., Lund, J., and Medellín-Azuara., J. (2019). Domestic well reliability: evaluating supply interruptions from groundwater overdraft, estimating costs and managing economic externalities. Hydrogeology Journal, 27.4 1159-1182.

[10] Greene C., Climate vulnerability, Drought, Farmworkers, Maladaptation, Rural communities. (2018). Environmental Science and Policy 89283–291. ISSN 18736416.

[11] Hanak, E., Lund, J., Dinar, A., Gray, B., and Howitt, R. (2011). Managing California’s Water: From Conflict to Reconciliation. Public Policy Institute of California. ISBN9781582131412.

[13] Johnson, T. D., & Belitz, K. (2015). Identifying the location and population served by domestic wells in California. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies, 3, 31-86.

[14] Johnson, T. D., & Belitz, K. (2017). Domestic well locations and populations served in the contiguous US: 1990. Science of The Total Environment, 607, 658-668.

[15] Journel, A. G., & Huijbregts, C. J. (1978). Mining geostatistics (Vol. 600). London: Academic press.

[16] Laurent, A. G. (1963). The lognormal distribution and the translation method: description and estimation problems. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(301), 231-235.

[17] Lobell, D. B., Schlenker, W., & Costa-Roberts, J. (2011). Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science, 333(6042), 616-620.

[18] Lopez, A., Tebaldi, C., New, M., Stainforth, D., Allen, M., & Kettleborough, J. (2006). Two approaches to quantifying uncertainty in global temperature changes. Journal of Climate, 19(19), 4785-4796.

[19] Medellín-Azuara, J., MacEwan, D., Howitt, R., Sumner, D.A., Lund, J., Scheer, J., Gailey, R., Hart, Q., Alexander, N.D., and Arnold B. (2016). Economic Analysis of the California Drought on Agriculture: A report for the California Department of Food and Agriculture. Center for Watershed Sciences, University of California Davis. Davis, CA.

[20] Mitchell, D., Hanak, E., Baerenklau, K., Escriva-Bou, A., Mccann, H., Pérez-Urdiales, M., and Schwabe, K. (2017). Building Drought Resilience in California's Cities and Suburbs. Public Policy Institute of California. SAn Francisco, CA.

[21] Pauloo, R., Fogg, G., Dahlke, H., Escriva-Bou, A., Fencl, A., and Guillon, H. (2020). Domestic well vulnerability to drought duration and unsustainable groundwater management in California’s Central Valley. Environmental Research Letters, 15.4 044010

[22] Perrone, D., & Jasechko, S. (2017). Dry groundwater wells in the western United States. Environmental Research Letters, 12(10), 104002.

[23] Perrone, D. and Jasechko, S., Deeper well drilling an unsustainable stopgap to groundwater depletion. (2019). Nature Sustainability, 2773–782

[24] Rhoades, A. M., Jones, A. D., & Ullrich, P. A. (2018). The changing character of the California Sierra Nevada as a natural reservoir. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(23), 13-008.

[25] Sophocleous M., From safe yield to sustainable development of water resources—the Kansas experience., (2000). Journal of Hydrology, 23527–43.

[26] Sustainable Groundwater Management Act. (2014). California Water Code sec. 10720-10737.8

[27] Swain, D. L., Langenbrunner, B., Neelin, J. D., & Hall, A. (2018). Increasing precipitation volatility in twenty-first-century California. Nature Climate Change, 8(5), 427-433.

[28] Theis, C.V., (1935). The relation between the lowering of the piezometric surface and the rate and duration of discharge of a well using ground-water storage., Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 16519–52.

[29] Theis, C.V., (1940). The source of water derived from wells., Civil Engineering, 10277–280.

[30] Tullis, J. Paul. (1989). Hydraulics of pipelines: Pumps, valves, cavitation, transients. John Wiley & Sons.

[31] Williams, A. P., Seager, R., Abatzoglou, J. T., Cook, B. I., Smerdon, J. E., & Cook, E. R. (2015). Contribution of anthropogenic warming to California drought during 2012–2014. Geophysical Research Letters, 42(16), 6819-6828.

[32] Varouchakis, E. A., Hristopulos, D. T., & Karatzas, G. P. (2012). Improving kriging of groundwater level data using nonlinear normalizing transformations—a field application. Hydrological Sciences Journal, 57(7), 1404-1419.

In addition to the web tool data viewer, GSP Well Failure data is available for downloaded via static files and can be accessed programmatically via a scripting language. R and Python examples below are provided below.

The well failure model in this study is implemented in R, and openly available on Github.

The Well Completion report database can be downloaded from the California Natural Resources Agency's Online Well Completion Report Database (OSWCR).

https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/well-completion-reports

The subset of 15,368 domestic wells considered in this study are provided below.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| wcr_number | Well Completion Report Number from the Well Completion report database, https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/well-completion-reports |

| mean_ci_upper | Upper 95% CI of estimated pump location in feet below land surface from Pauloo et al., (2020) |

| pump_loc | Estimated pump location in feet below land surface from Pauloo et al., (2020) |

| mean_ci_lower | Lower 95% CI of estimated pump location in feet below land surface from Pauloo et al., (2020) |

| tot_completed_depth | Total completed depth of well in feet below land surface from the Well Completion report database https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/well-completion-reports |

| gwl_2019 | Initial groundwater level condition (2019 average) at the well in feet below land surface, calculated via ordinary kriging from ambient seasonal groundwater level measurements in the Periodic Groundwater Level Measurement Database https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/periodic-groundwater-level-measurements |

| gsp_name | name of the GSP the well is within |

| year_drilled | year the well was drilled |

| x | x coordinate of the well in EPSG 4269 |

| y | y coordinate of the well in EPSG 4269 |

GSP spatial boundaries for the GSPs examined in this study were downloaded from the State of California's GSP Map Viewer, which provides all GSP spatial boundaries in full.

https://sgma.water.ca.gov/webgis/index.jsp?appid=gasmaster&rz=true

The GSPs considered in this study are: Buena Vista (Kern), Central Kings, Chowchilla, East Kaweah, East Tule, Eastern San Joaquin, Grassland (DM), Greater Kaweah, James (Kings), Kern Groundwater Authority, Kern River, Kings River East, Lower Tule River, Madera Joint, Mc Mullin, Merced, Mid Kaweah, North Fork Kings, North Kings, Northern Central (DM), Pixley (Tule), SJREC (DM), South Kings, Tulare Lake, and Westside.

Two groundwater level surfaces were developed via ordinary kriging for this study. They include a 2019 groundwater level initial condition, and a minimum threshold surface, as described in the Methodology.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| gwl_2019 | Initial groundwater level condition representing the average 2019 groundwater level in the GSPs considered in this study. Values reported are in feet below land surface. |

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| gwl_mt | Groundwater level condition representing the minimum threshold surface specified by individual monitoring locations in the GSPs reviewed by this study. Values reported are in feet below land surface. |

The 2019 groundwater level initial condition was derived from individual groundwater level measurements available for download in full from the California Natural Resources Agency's Periodic Groundwater Level Measurement Database.

https://data.cnra.ca.gov/dataset/periodic-groundwater-level-measurements

Well failure model results are available for interactive visual inspection on the Map page, and can be downloaded below.

well_failure_model_results.csv, 40MB

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| wcr_number | Well Completion report number to join to domestic_wells.csv |

| high_n | Well status (active or failing) for the pump location 5% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| lowering_cost_high_n | Cost in $USD to lower the well for the pump location 5% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| deepening_cost_high_n | Cost in $USD to deepen the well for the pump location 5% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| low_n | Well status (active or failing) for the pump location 95% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| lowering_cost_low_n | Cost in $USD to lower the well for the pump location 95% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| deepening_cost_low_n | Cost in $USD to deepen the well for the pump location 95% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| total_cost_high_n | Total cost in $USD to lower and deepen the well for the pump location 5% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

| total_cost_low_n | Total cost in $USD to lower and deepen the well for the pump location 5% confidence interval at n feet of decline |

library(tidyverse)

library(raster)

library(sf)

# urls

url_dw <- "https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/domestic_wells.csv"

url_mr <- "https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/well_failure_model_results.csv"

url_g1 <- "/vsicurl/https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/gwl_2019.tif"

url_g2 <- "/vsicurl/https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/gwl_mt.tif"

# read domestic well data and model results

domestic_wells <- read_csv(url_dw) %>% st_as_sf(coords = c("x", "y"), crs = 4269)

model_results <- read_csv(url_mr)

# read 2019 groundwater level and MT surface

gwl_2019 <- raster(url_g1)

gwl_mt <- raster(url_g2)

# the above code may not work depending on how your spatial packages are configured

# in this case, download the files and open them like so:

temp1 <- temp2 <- tempfile()

download.file(url_g1, temp1); download.file(url_g2, temp2)

gwl_2019 <- raster(temp1)

gwl_mt <- raster(temp2)

import pandas as pd

import rasterio

# urls

url_dw = "https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/domestic_wells.csv"

url_mr = "https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/well_failure_model_results.csv"

url_g1 = "/vsicurl/https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/gwl_2019.tif"

url_g2 = "/vsicurl/https://github.com/richpauloo/aife/raw/master/download/gwl_mt.tif"

# read domestic well data and model results

domestic_wells = pd.read_csv(url_dw)

model_results = pd.read_csv(url_mr)

# read 2019 groundwater level and MT surface

gwl_2019 = rasterio.open(url_g1)

gwl_mt = rasterio.open(url_g2)

The GSA Well Failure website is available for use under the Open Database License.

The website and all of the data herein are provided “as is” and “as available” without warranty of any kind either express or implied, including but not limited to the implied warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, freedom from contamination by computer viruses and malware, and non-infringement. Water Data Lab makes no warranty as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of any data available through the database and the website. You are responsible for verifying any information before relying on it. Use of the website, database, and the data is at your sole risk. If you have obtained data from a source other than https://gspdrywells.com, be aware that electronic data may be altered subsequent to the original distribution. Data can also quickly become out-of-date.

To the maximum extent permitted by law, Water Data Lab disclaims all liability, whether based in contract, tort (including negligence), strict liability or otherwise, and further disclaims all losses, including without limitation indirect, incidental, consequential, or special damages arising out of or in any way connected with access to or use of the website, database, or the data even if Water Data Lab has been advised of the possibility of such damages.

We recommend the following citation when using or referencing this dataset:

Pauloo, R., Bostic, D., Monaco, A. and Hammond, K. 2021. GSA Well Failure: forecasting domestic well failure in critical priority basins. Berkeley, California. Available at https://www.gspdrywells.com. (Date Accessed)

This tool was created to show you, the user, how groundwater management decisions will impact homes with domestic wells in the San Joaquin Valley. Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (“GSAs”), created following the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014, are in charge of how groundwater is used and managed. Policy decisions made by GSAs, and codified in Groundwater Sustainability Plans (“GSPs”), will either protect domestic wells or allow them to go dry.

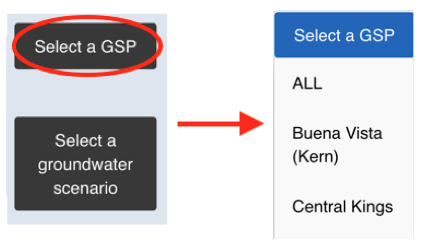

(1) Select the GSP that is most relevant to you. You may also select “All GSPs,” which will show you results for all 25 of the GSPs included in this tool.

(2) Select between the options of groundwater levels and scenarios. You have the option of choosing the “minimum threshold” that the GSA has specified in its Groundwater Sustainability Plan, or GSP. You may also choose how many feet below the 2019 groundwater levels you want to see. For example, you can choose to see how many wells will go dry if the water in the aquifers is lowered by 10 feet, 20 feet, and more, up to 300 feet.

(3) Based on your selections, the tool will show you how many domestic wells are likely to go dry in that scenario for the GSA(s) you selected.

If you do not know what Groundwater Sustainability Agency is relevant to you, search for your address using the Department of Water Resources' GSP Map Viewer Tool.

Controls are labeled in the image and described below:

Groundwater level decline, Well failure count, Well failure percent, and Cost estimate for the selected scenario. Click buttons to read more.On the main page showing all GSP areas, click on a GSP region in the map to view the forecasted well failure plot for the selected GSP, and hover over the plot to view failure and cost statistics for each scenario.